Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

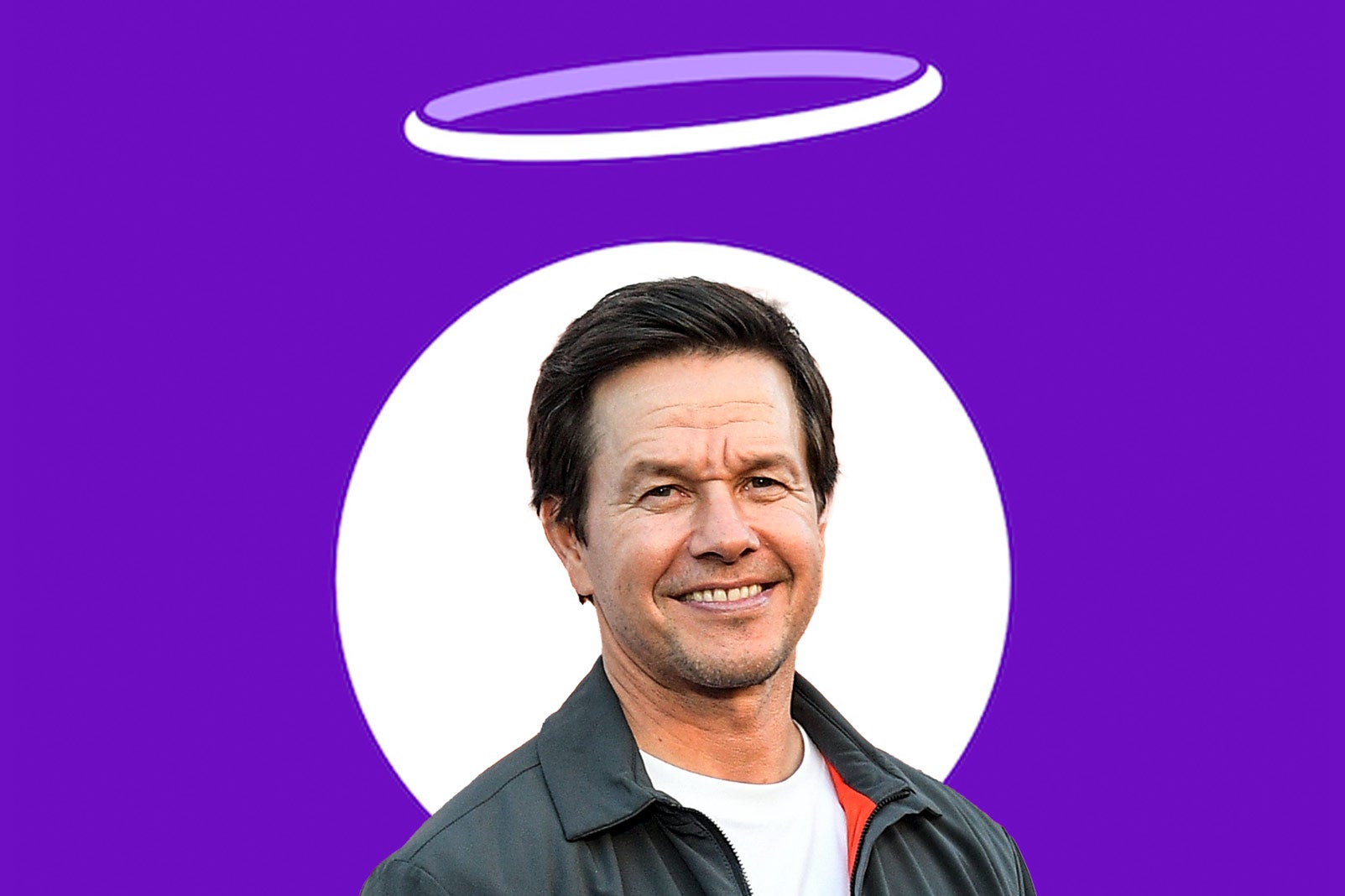

While the world said goodbye to Pope Francis on Easter Monday, I was bidding farewell to a very different Catholic spokesman: Mark Wahlberg. Forty days and 40 nights earlier, I had downloaded Hallow, the self-described “#1 prayer app in the world” promoted by the actor and hamburger impresario. After purchasing its premium subscription, I dedicated my Lent to an immersive exploration of the app—a sort of digital pilgrimage to a cathedral of gamified spirituality. Now, with Easter over, my crusade was at an end.

My mission, when I explained it to people, was met with a classic theological question: “Why?” Yes, like Wahlberg, I was raised in a deeply Irish Catholic community. But today I do not, as the actor would put it, “stay prayed up.” And though I like The Perfect Storm and Daddy’s Home, I don’t typically look to Mark Wahlberg for guidance on bringing glory to Christ. Was this a joke? Was I bored with Candy Crush? Did a burning bush instruct me to ride into the app store and denounce the commodification of religion, in a table-turning sermon worthy of Matthew?

Mostly, I was curious. What was this enigmatic spiritual app Wahlberg was willing to promote on his Instagram, in between posts about his Flecha Azul tequila? The best way to learn would be to try it myself. But beneath that curiosity were more pointed motivations; I did want to take a critical look under the monastic hood of Hallow. A 2022 BuzzFeed News report on a similar app, Pray.com, revealed they had shared users’ granular data (think: your literal thoughts and prayers) with “third parties” for “commercial purposes.” (A representative for Pray.com reached out to Slate for clarification, stating, “Pray.com strives to follow best practices and industry standards with regard to privacy and security. … Pray.com is not in the business of selling its customers’ data.”) Hallow responded to that reporter that they hadn’t yet shared user information for marketing purposes, but their policy still reserves the right to do so. And their judgment can’t entirely be trusted given Hallow’s history of hiring controversial stars. Moreover, the private monetization of prayer has raised new versions of timeless ethical questions. Is Hallow’s $69.99-a-year charge a step back into pre-Lutheran indulgences? Or literal business as usual for Christianity, a religion whose denominations remain one of the world’s largest land owners, invented televangelism, and repeatedly tried to sell young me Bibleman tapes?

I had a personal investment, too. I was compelled to try Hallow as a lapsed Catholic. I was baptized. My family attended Sunday Mass. I took catechism classes Tuesday evenings and briefly attended St. Joseph’s Catholic School (until the tuition became too expensive). In a way, I’d even say Mark Wahlberg and I are brothers, because that might mean he’d help me open a burger restaurant, too. Today, by contrast, my engagement with Catholicism has been mostly limited to Christmas and Easter, give or take a baptism or Cranberries album. Could using Hallow, even with a skeptical eye, reconnect me to that preteen acolyte who went to Mass?

Every Catholic gives up something for Lent. For me, it would be my free time, which would be spent answering this question as I submerged myself in the healing e-waters of snackable salvation and joined Hallow.

With prayer stats like that, who knows what I was missing?! I dive in on the app’s more traditional biblical content, like Hallow’s “Daily Reading.” That day it’s an Old Testament passage from the Prophet Ezekiel. Powerful stuff, but not exactly “exclusive online content,” considering the Holy Bible is the most widely available book in the history of written language. Fortunately, my next pick is a gem: “Daily Reflections with Jeff Cavins,” a video series hosted by Cavins, a biblical scholar and, arguably, Catholic network EWTN’s biggest star (not counting Jesus).

Perhaps it was divinely ordained that I got served someone who wasn’t Wahlberg first, prompting me to wander away, because Cavins turns out to be one of the most entertaining people on Hallow (and not just because past alternatives include QAnon theorist Jim Caviezel). Cavins has a short white beard that reminded me of Martin Mull. During a series of episodes shot in the Holy Land, he wears an adorable Indiana Jones fedora. He has the energy of my dad on vacation, nose buried in a guide book. My theory is that, as an actual biblical scholar, Cavins didn’t feel the need to put on the same kind of sanctimonious airs as his celebrity colleagues. Of course, the guy’s still a staunch Catholic, with views I deeply disagree with. Put the two of us at an IRL Easter brunch together, and that conversation could get real uncomfortable, real fast. But relative to other Hallow figures, at least, Cavins comes off as more interested in the historical Jesus than trying to convince me why premarital sex is evil.

Not that I didn’t want more star power. And, finally, I get it. Wahlberg eventually makes his Pray40 debut. His appearances, it seems, would be limited to “Fasting Fridays.” Wahlberg dictating Hallow users’ diets is a natural role, since many of his Instagram videos show the actor describing his giant breakfasts while his long-suffering chef, who’s probably been up since 3 a.m., stands wearily nearby. “Welcome to Fasting Fridays,” says Wahlberg. “It’s an honor to join you this Lent.” Each Friday, he tells me, he will introduce a new “fasting challenge.”

Then he throws a curveball and introduces “my friend, Chris Pratt.” I raise an eyebrow. Star-Lord was gonna speak for the actual Lord on Hallow? I thought he belonged to that church founded by the pastor Justin Bieber used to bring on his tour—not, so far as I know, a Catholic one? Mark Wahlberg hadn’t surprised me this much since the final shot of Boogie Nights. Chris would be helping us fast “since, as an Avenger, he knows a thing or two about discipline,” Wahlberg says. “Though, for the record, I can still take him,” he adds. “Sorry, I had to get that out there. I guess we’ll have to pray that Litany of Humility a few more times.” I wonder if a sentence had ever before contained so much Boston.

Pratt delivers a reading from the Gospel According to Mark (“I believe. Help my unbelief”), then Wahlberg delivers his first (fasting) challenge to the listener. He asks me to “fast from noise.” Specifically, he suggests I “put my phone down” more, somehow unaware that Hallow itself is on my phone.

My own “unbelief” is severely piqued by some of Hallow’s advocates. Wahlberg is an investor in Hallow, and every message he delivers seems undercut by the feeling that he’s not offering it out of the goodness of his heart; he’s working to drive up the value of his investment. Passion of the Christ star Caviezel, a Hallow spokesman and host of the app’s “Stations of the Cross” feature, can’t stop supporting QAnon conspiracies, including the theory that Democratic politicians run a secret child sex-trafficking cabal. Peter Thiel doesn’t preach on the app, but his statements elsewhere can read like the incoherent rants of someone speaking in tongues, from his warnings about the deep state and the dangers of a “globalist future,” to his speech at an event called “Hereticon,” where, according to Vanity Fair, Thiel “spoke about the coming of the Antichrist” (maybe he was referring to rumors of Gawker’s second return). The idea that Hallow is accountable to celebrities with these beliefs feels opposed to the company’s public statements, which say its goal is to “make Hallow as welcoming, inclusive, and non-judgmental a place as possible.” On the other hand, as Ainsley Earhardt told Pratt in a Fox & Friends interview, “You all are making it really cool to pray!”

Objectionable as its benefactors may be, you can’t say Hallow isn’t putting money into its product. As my Lent with Hallow continues, I am overcome with the sheer amount of features the app has. Too many to review here. There’s a feature that takes you through the rosary, daily Scripture, and the catechism. There’s Catholic meditation, Catholic music, a Catholic sleep “Praylist” (10 hours of “peaceful instrumental hymns”), and Catholic trivia. There’s a series called “Bible in a Year,” which, I’m gonna level with you, Hallow: If I had the discipline to read the entire Bible, I wouldn’t be getting my religion through a glorified Duolingo. There’s content for children, for teens, and one for dads called “Be-dad-itudes.” You can listen to Christian content from Gwen Stefani, Saved by the Bell actor Mario Lopez, a Cleveland Browns quarterback, outdoorsman Bear Grylls, or Liam Neeson, who reads selections from the works of C.S. Lewis, in case you really want to hear Mere Christianity delivered like a threat from a vindictive CIA agent.

Amid this absolute deluge of content, Wahlberg and Pratt continue giving us installments of Fasting Fridays. One afternoon in early April, after listening to an episode, I notice a quote on the screen:

Every time you encounter a trial, every time you encounter an opportunity to deny yourself, remember: Enter into the wounds of Christ crucified.

—Mark Wahlberg

Below the quote is an option to share it with my friends. I sigh. I had been keeping my journey mostly private, unsure how those close to me would react to their friend’s sudden Catholic zealotry. But if I was going to report on the full Hallow experience, I couldn’t deliberately avoid certain features out of fear or embarrassment. As a brave prophet once said, “Every time you encounter a trial, you enter into the wounds of Christ.” I pull up two friends from my contacts. A few clicks later, each of them receive, apropos of nothing, a message from me with a message from Mark Wahlberg, essentially asking them to accept Jesus Christ as their personal Lord and savior.

“Pat, is this spam?” replies Friend One. I reply it is not, and explain how I’m spending Lent. I never hear back.

Friend Two seems slightly more interested, or at least engaged enough to offer constructive criticism: “I can’t help hearing this in Mark Wahlberg’s voice.”

Not long after Laetare Sunday (the fourth Sunday of Lent), I want to explore the app’s more interactive features, and its most interactive was “Magisterium,” Hallow’s A.I. chatbot. Yes, even God uses ChatGPT now. I’m skeptical, but after three weeks of listening to Hallow’s pastors quote Scripture at me, the idea of getting to ask some questions, even to a digital mass of mysterious data, is a welcome relief.

“Do you have a question about the faith?” asks Magisterium.

“Are you like a priest?” I type.

“No, I am not like a priest,” it replies. “I am designed to provide accurate answers based on Catholic teachings, using a compound AI system that integrates multiple technologies, a vast content library, and regularly updated language models to ensure fidelity to Catholic Tradition.”

Honestly, not the most boring sermon I’ve ever heard. “OK, I think I understand,” I write. “Who was the tallest pope?” It was a softball question, a journalistic tactic to build trust with my interview subject. I really wanted Magisterium to like me.

“My apologies, I need to be more specific,” says the program, and offers a list of odd alternatives, like, “Does height affect papal authority?” and “What are the Church’s views on height?” Huh. This chatbot wanted to turn my objective pub-trivia question into a theological argument. What started as a playful chat had become an inquisition. I feel like Domhnall Gleeson in Ex Machina. Who was studying who here?

Come to think of it, I wonder, why would Hallow embrace artificial intelligence at all? It had been a while since I read my Genesis, but I was pretty sure it didn’t allow God to have competitors in the life-creation business. On the other hand, thinking about evangelicals’ growing embrace of President Donald Trump over the past several years, I believe it is a strange time for, well, belief. Hallow’s existence is indicative of a larger merging of Silicon Valley and conservative Christianity. Just like our biggest tech CEOs have bowed to Trump—donating hundreds of millions in campaign dollars to the president and his favorite candidates—they’ve also started courting religious groups more aggressively. Elon Musk has called himself a “cultural Christian,” and in 2021, Mark Zuckerberg’s Facebook added a Hallow-like tool called “Prayer Posts.” The introduction of new Facebook features and the world’s richest man identifying as a “cultural Christian” themselves may be minor events. But the idea of Big Tech co-opting the intimate nature of faith, a phenomenon literally personified by the religious chatbot before me, is enough to shake me to my core.

On the other hand … what were the Church’s views on height?! I shrug and click on Magisterium’s question.

“All physical attributes are part of the human person created in God’s image and should be respected as such,” replies Magisterium.

In principle, I agree with respecting all physical attributes of the human person. I let out a sigh of relief, having narrowly avoided a schism between man and machine. I type a final question: “How much is Hallow worth?”

Somewhere in the bowels of a server farm, Magisterium sorts through an unimaginably vast trove of information and arrives at its answer: “I was unable to find specific information on the exact net worth or valuation of Hallow.”

Incredibly, Hallow had developed a chatbot that can explain the nature of God but can’t look up financial news.

The end of Lent approaches. After countless hours of sermons and rosaries and Christian rock playlists and beatitudes and Be-dad-itudes, I’m ready for a break. Even my boy Jeff Cavins and his fedora have outstayed their welcome. But what have I learned? On a practical level, not much, at least not according to the app’s daily biblical quizzes I keep flunking. (The betrayal of Jesus for 30 pieces of silver fulfills a prophecy found in Zechariah, not Psalms, you idiot!) I couldn’t say I felt more in touch with my Catholic upbringing, but the app’s content didn’t frighten me, either. Even Jim Caviezel managed to get through his appearance without accusing me of supporting an adrenochrome-harvesting pedophilia cabal. Thanks?

Amid all the big changes he enacted in his 12 years on St. Peter’s throne, Pope Francis also started the first papal Twitter account. It was a relatively minor change, but @Pontifex and its ability to connect the Pope to his public demonstrated that a religion engaging with a tech company—even a for-profit one—isn’t inherently bad. What is troubling about Hallow, I think, isn’t the message it’s spreading, but the growing strength of the institutions needed to spread it. Shortly before Hallow received its investment from Peter Thiel in 2021, one minister interviewed by the New York Times about Facebook’s push to partner with churches warned of the dangers in trusting our faith to any tech platform “that is susceptible to all the whims of politics and culture and congressional hearings.” My 40 days and 40 nights playing with Hallow didn’t give me any profound insight into this danger. But learning about the money, the institutions, and above all the people behind the app reminded me how powerful, wealthy, and influential the Catholic Church remains, and how that influence can help and comfort, as much as it can exploit and terrify.

In that way, at least, my time with Hallow did feel like going to Mass again.

Update, May 5, 2025: This article has been updated to include comment from Pray.com.