War, policy, civil rights, labor conditions, racism — when Madisonians want their voices heard on issues like these, they march in the streets, stage sit-ins and raise their picket signs in protest. These collective actions might not always result in the change that’s being called for, but they serve as historical markers of moments when we couldn’t sit back and be silent.

The way these protests affected and defined Madison proves yet again that the University of Wisconsin–Madison is the most important thing about the city. Of the demonstrations listed in this article, only two — against Gov. Scott Walker’s Act 10 assault on public employees in 2011 and for Black lives in 2020 — weren’t driven by UW–Madison students.

The issues that sparked the protests were mostly those that arose in many other college towns, with most concerning the war in Vietnam, followed by racism and its effects. Only two protests — over the State Street Mall and the wrong-way bus lane — were about issues unique to Madison.

Certain actions — primarily the Black Studies Strike of 1969 and the anti-sweatshop actions of 1999-2000 — succeeded because they followed two of the cardinal rules of protest: They targeted local decision-makers and articulated clear demands. Their tactic: meaningful inconvenience with the potential for more, but no outright vandalism.

Even small numbers can attain big results. With a core of only about 35 people, and never more than about 100, the sweatshop protests still forced documented, meaningful progress.

This timeline outlines notable demonstrations spanning 74 years — where we disrupted, faced arrest, blocked doorways, remained peaceful, illegally encamped, joined hands, sang, chanted, cried, ran from tear gas or rioted — in Madison’s history.

Lunch Counter Segregation

Feb. 27, 1960

A group of young white leftists picketed the F.W. Woolworth and W.T. Grant stores on Capitol Square, supporting the month-old sit-in movement challenging lunch counter segregation in the Southern outlets of their national chains. Intermittent picketing continued into the summer.

The First Disruptive Protest

April 21, 1961

Several hundred conservative students staged an hourlong disruption inside Wisconsin Union Theater (now known as Shannon Hall), breaking up a Socialist Club rally protesting American involvement in the failed Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba.

Anti-War Protests Start

Oct. 18, 1963

Seven liberal and leftist groups organized the city’s first demonstration against the war in Vietnam, drawing a crowd of about 350 to the steps of Memorial Union.

Attempted Arrest of a Base Commander

Oct. 16, 1965

Nine men and two women from the Committee for Direct Action to End the War in Viet Nam (sic) were arrested for obstructing the entrance to the Truax Air Force Base while attempting to arrest the base commander for “crimes against humanity.”

Anti-Draft Action

May 16-20, 1966

An impromptu anti-draft action by Madison Students for a Democratic Society, or SDS, to occupy the administration building quickly grew to a five-day, nonobstructive sit-in supporting the demands of the Committee on the University and the Draft, or CUD. The committee demanded that the university stop providing a class rank and administering a standardized test, which the Selective Service used to grant 2-S deferments that kept students out of the war. CUD wanted to galvanize middle-class families by increasing the threat to their sons. Although ending the test and not providing a class rank would have exposed all male students to the draft and Vietnam, the Wisconsin Student Association Senate and the Interfraternity Council endorsed CUD’s demands — creating an unprecedented coalition of geeks, Greeks and freaks. UW–Madison President Fred Harvey Harrington and Chancellor Robben Fleming had words of praise and promise for a Bascom Hill crowd of about 8,000 on Wednesday, and protesters felt on the verge of victory when the siege ended Friday — making their disappointment more painful when the faculty rejected CUD’s demands on Monday. The regents thought the episode bolstered the university’s prestige, but student trust in campus leadership was shattered.

The Ted Kennedy Section

Oct. 27, 1966

The reaction was swift and harsh when leaders and supporters of the Committee to End the War in Viet Nam heckled Sen. Edward "Ted" Kennedy off the Stock Pavilion stage at a gubernatorial campaign event for Lt. Gov. Patrick Lucey. Afterward, more than 8,000 students signed an apology, and the Wisconsin Student Association Senate put the committee on “provisional status.” The faculty declared that those attending a campus program “have the duty not to obstruct it,” and that deliberately interfering with a university-sanctioned speech “may constitute grounds” for discipline, including suspension and expulsion. The rule’s sponsor called this “the Ted Kennedy section.” The following October, the rule would be put to historic use at the Battle of Dow.

Beauty Queen Gets Hit By a Bus

May 17-18, 1967

When the reconstructed University Avenue opened in November 1966 with an eastbound bus lane on the south (odd-numbered) side of the street going against four lanes heading west, everyone worried that students focused on crossing those four lanes would fail to heed the lane heading east. Tragedy struck on March 1, 1967, when an eastbound bus hit and dragged campus beauty queen Donna Schueler, forcing the amputation of her left leg. The city still refused to move the buses to the newly expanded, one-way eastbound West Johnson Street.

On May 17, 1967, a militant group took control of an otherwise legal protest march along the University Avenue sidewalk and used their bodies and bicycles to block an eastbound bus at Brooks Street, starting a roaming three-hour skirmish during which police arrested 25 people, including graduate student and Wisconsin Student Association Senator Paul Soglin, who would later become Madison mayor. The city traffic commission voted to install two more traffic lights and a barrier to prevent midblock crossing but kept the wrong-way bus lane until April 1979, when it was repurposed for bicycles. The buses moved to Johnson Street.

The Battle of Dow

Oct. 18, 1967

The Battle of Dow on Thursday, Oct. 18, 1967, was the most important political protest in Madison history. Marked by police brutality, the unprecedented use of tear gas and a student counterattack, it radicalized thousands, awakened the broader community to anti-war unrest, helped push Soglin into greater prominence and led to the 1969 Mifflin Street Block Party Riots.

Targeting Dow Chemical because it made the military’s flammable gel, napalm, the Ad Hoc Committee to Protest Dow Chemical planned a day of peaceful picketing followed by a disruptive occupation inside the Commerce Building to block job interviews — something explicitly forbidden by "the Ted Kennedy section” rule of October 1966.

Obstructors anticipated arrest and university discipline. Almost all planned to go limp if arrested, as at civil rights sit-ins of the early 1960s. Some would actively resist arrest.

By 11 a.m., about 250 active obstructors, and just as many supportive onlookers, had packed the Commerce Building’s narrow first floor hallway. UW Police Chief Ralph Hanson tried using diplomacy to clear the building. That failed, and he got Chancellor William Sewell’s permission to call for city police to enforce the Ted Kennedy rule.

Hanson gave a final plea and warning, which few heard. Some linked arms, and a few wrapped belts around their fists as makeshift leather brass knuckles in case a fight broke out.

Outside, Madison officers removed their badges (for safety, they later claimed; though possibly in preparation to fight anonymously). Most were east siders who resented the students, seeing them as pampered and unpatriotic. The riot squad was restless and untrained, with a confused mission.

Everything went wrong. When their first foray into the foyer failed, they regrouped and charged back in. Hanson was outside and couldn’t restrain them.

Flailing away with 2-foot wooden nightsticks, police weren’t arresting students, they were beating them bloody and throwing them into the Commerce courtyard. Soglin, who wasn’t considered an anti-war leader, was among more than 45 protesters sent to the emergency room after suffering lasting damage to his spine.

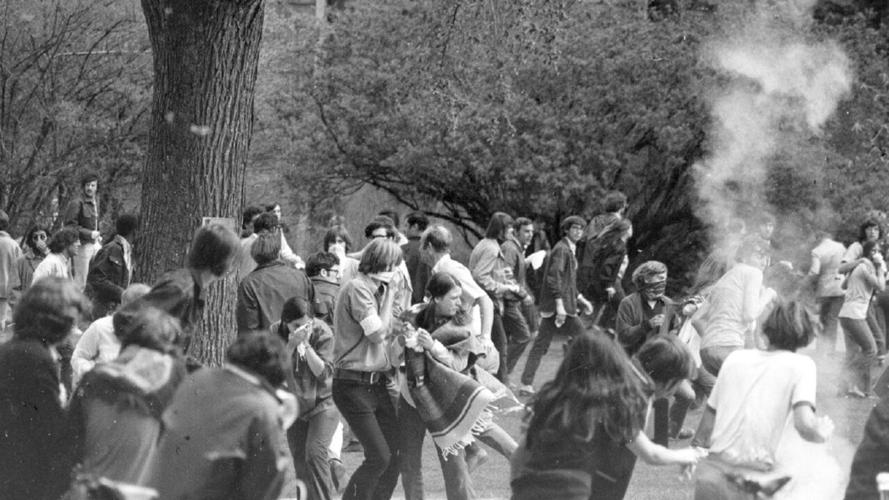

Police cleared the building in 13 minutes but now faced thousands of enraged students filling the plaza. Bricks and bottles flew, and several officers were seriously injured. When the 1:20 p.m. classes got out, the crowd grew to about 5,000. Police Chief Wilbur Emery called for reinforcements and deployed tear gas — marking its first use during an anti-war protest on any college campus. The wind sent it swirling, affecting — and radicalizing — many previously uninvolved observers.

The chaos continued until 150 officers established a firm perimeter around Commerce at about 4:30 p.m.

The next morning, about 2,000 attended a Library Mall rally of the new Committee for Student Rights, which Soglin briefly co-chaired. A short CSR strike had only slight success (reported absences were only marginally above normal), but Soglin became prominent among the newly radicalized and was invited to represent the movement at off-campus forums. Six months later, he was elected to the Madison City Council as its first radical alder.

On Thursday, the faculty endorsed Sewell’s decision to call city cops and rejected a resolution condemning police violence. Students who were disappointed after the 1966 draft sit-in now felt totally betrayed.

In November, the regents voted that obstructing job interviews would be “considered misconduct meriting the most severe disciplinary penalties of the university.”

With more than a dozen officers suffering injuries ranging from black eyes and broken bones to a damaged larynx, an embarrassed Chief Emery angrily resolved to respond with overwhelming force at future incidents. That’s why, in May 1969, officers responded to a noise complaint on Mifflin Street in riot gear, helping spark a three-night riot.

Although the vast majority of the Commerce obstructors planned to let police carry their limp bodies out, university administrators concluded otherwise. Assuming in later encounters that protesters would actively resist arrest, they acted accordingly. For its part, the anti-war movement decided that with the university’s blessing, the police had attacked entirely without cause or warning and would do so again.

Years of escalating violence by both sides would flow from these perceptions.

The Black Studies Strike

Feb. 7-18, 1969

A weeklong conference on “The Black Revolution: To What Ends?” helped spark 12 days of disruption and led to the creation of the Department of African American Studies, making the Black Studies Strike the most successful political protest of the ’60s.

The strike began on Friday, Feb. 7, shortly after the Black People’s Alliance and other Black student leaders issued the wide-ranging “Thirteen Demands,” which the Rev. Jesse Jackson endorsed “to the letter” in a conference speech that night. The strike’s Black leaders made unprecedented inroads with the previously apolitical residents of the Southeast Dorms, who joined the Students for a Democratic Society and other radicals in blocking the doors to several campus buildings. After a few days, local law enforcement was run ragged. Gov. Warren Knowles activated more than 2,000 National Guard members, who kept buildings open but triggered a defensive response that caused strike activity to spike sharply. The day after the Guard arrived, close to 7,000 strikers under the disciplined direction of Black marshals blocked University Avenue four times in two hours, until they were removed by police with clubs and tear gas and Guard members with fixed bayonets. That night, around 9,000 students held an orderly torchlit march from campus to the Capitol and back. The strike ended on Feb. 18. A week later, a special faculty committee recommended the creation of an autonomous, degree-granting Black Studies Department (later named the Department of Afro-American Studies), the most important of the Thirteen Demands. The faculty endorsed the proposal, the regents approved it and the department opened in September 1970.

Moratorium Night

Oct. 15, 1969

Fifteen thousand people filled the UW Fieldhouse for a series of anti-war speeches — the largest protest crowd of the era — then marched up State Street through the cold rain, with lit candles under wet umbrellas. At the Capitol, the Grace Episcopal Church bell tolled for the more than 900 Wisconsin servicemen who had died in the war so far. As each name was read, a candle was extinguished.

The City Burns

Spring semester, 1970

This was a violent time in downtown Madison. On Feb. 12, a demonstration against General Electric job recruiters turned into a fist-swinging, rock-throwing, glass-breaking rampage by about 2,000 anti-war activists. It caused about $50,000 in damages at 22 downtown businesses and four campus buildings. On April 18, a peaceful march and Capitol rally by about 8,000 burst into violence when a self-styled “Revolutionary Contingent” of a few hundred stampeded down State Street and into the Miffland neighborhood, doing about $100,000 in damage to more than 35 businesses and the Madison Public Schools administration building. From May 4-9, President Richard Nixon’s incursion into Cambodia and the fatal shooting of four Kent State protesters by members of the Ohio National Guard sparked the worst sustained vandalism and violence in Madison history. For five consecutive nights, the city and campus endured 20 major firebombings that resulted in about $270,000 in damage. The National Guard deployment cost $732,000. The city spent $190,000 on policemen and munitions, including for the powerful CS gas canisters officers fired into the Mifflin Street Co-op and the UW Hillel, which was then operating as a recognized medical center for people injured during the protests.

First Anniversary of Cambodia/Kent State

May 5-6, 1971

Anti-war activists marked the first anniversary of Cambodia/Kent State with two nights of rallies, marches and hit-and-run guerilla warfare that left downtown windows shattered and the lower campus saturated with tear gas. On May 6, during nearly three hours of skirmishes involving up to 2,000 people, radicals threw rocks from roofs and windows and set fires. Police fired tear gas into the Memorial Union and Hillel Foundation. There were 24 arrests and 14 reported injuries.

State Street Mall

March 18-20, 1972

In August 1971, city council supporters of a State Street mall succeeded in closing the last two blocks for a six-month trial period to evaluate the impact on traffic. When the test ended and the city moved to reopen the street, students who wanted it to stay pedestrian-only started a three-day protest culminating in a 10-hour melee as a crowd of 3,000 marched and shattered windows in six stores. The next night, the council voted 15-7 to close the two blocks for a pedestrian mall — provided state and federal funding was assured — and limit the rest of the street to buses, bikes, emergency vehicles and cabs.

Second Anniversary of Cambodia/Kent State

May 4-11, 1972

Several thousand people of all ages marked the second anniversary of Cambodia/Kent State with a peaceful rally at the Capitol on May 4, 1972. But President Nixon’s announcement four nights later that he had ordered that explosive mines be dropped into North Vietnam’s main seaport, Haiphong harbor, sparked three days and nights of rallies, marches, smashing and trashing. Police responded with copious clouds of tear gas and an aggressive, sometimes unprovoked, use of wooden batons. On May 9, in the largest anti-war demonstration since the Moratorium events in October 1969, a crowd of about 10,000 marched from Library Mall to the Capitol. Thirty-three persons, ranging in age from 15 to 37, were arrested, most of them by undercover officers embedded in the crowds.

Sell the Stocks!

Nov. 11, 1977

UW Police used Mace inside Van Hise Hall to repel a Committee Against Racism cadre of about 75 who’d demanded to confront the regents about their decision to retain UW’s stocks in companies doing substantial business in South Africa — which Attorney General Bronson La Follette said they had to sell to comply with the state’s anti-discrimination statute. In February 1978, as divestment activists broke a locked door down the hall and scuffled with UW Police, the regents voted to sell the holdings — taking a $540,000 loss.

The Long Battle Surrounding ROTC

April 18-23, 1990

The longest-lived topic of protest in Madison has been Reserve Officer Training Corps, or ROTC, though the particulars have changed over time.

On May 11, 1950, 20 students picketed the formal ROTC military review inside Camp Randall to protest the requirement that all male students take ROTC courses during their first two years. After an interrogation during which they were not allowed counsel, 18 students were placed on disciplinary probation through the following semester and prohibited from holding any campus office or participating in publications or dramatic societies. ROTC became voluntary in 1960.

Protesting ROTC policy that excluded gays and lesbians, activists from the Bascom Coalition (at times numbering more than 150) staged a sit-in outside Chancellor Donna Shalala’s office from April 18-23, 1990, demanding she approve a paragraph in all applicable campus publications stating that ROTC policy contradicted the UW’s official policy banning discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. Shalala refused but supported a compromise by Dean of Students Mary Rouse to include a similar two-page letter in student orientation materials.

Anti-Sweatshop Success

1999-2000

Anti-sweatshop protests spanned countries and centuries, later spurring two years of action at UW–Madison. From Feb. 8-12, 1999, about 100 anti-sweatshop activists occupied the Bascom Hall rotunda and the area outside Chancellor David Ward’s office until he signed an agreement stating that the code of conduct for contractors who made apparel with the UW logo require them to disclose their factory locations, pay living wages as determined by a UW study and protect the rights of female workers. Activists rejoiced but soon soured on the university’s implementation.

On Wednesday, Feb. 16, 2000, a group of about 100 pounded on the outside walls of Ward’s office for hours and loudly demanded the university leave the sweatshop-monitoring Fair Labor Association due to its industry involvement. While inside, seven students had chained themselves together with bicycle locks. Ward agreed to withdraw from the FLA. A peaceful sit-in continued until Friday, when Ward agreed to their second demand: that the UW join the Worker Rights Consortium, albeit provisionally. When protesters issued a new major demand rather than leave as Ward had told them to, he authorized a predawn raid that Sunday, in which university and local police in riot gear made 54 arrests — more than at any protest in the ’60s or ’70s. Charges were later reduced to ordinance violations.

The Collective Bargaining Outcry

Feb. 14-March 12, 2011

Crowds ranging from 25,000 to more than 100,000 joined intermittent demonstrations at and inside the State Capitol to protest provisions in Gov. Scott Walker’s Budget Repair Bill, which eliminated collective bargaining for almost all municipal employees. Despite the massive outpouring — protests lasted until June 2011 before they significantly started to decline — the union-gutting section was enacted into law, and Walker comfortably survived a recall election in 2012.

The Murder of George Floyd

Spring and summer, 2020

The May 25, 2020, murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin sparked three days of peaceful protests and nighttime vandalism and looting, resulting in thousands of dollars in damages and lost inventory to small businesses; more than 40 arrests; a six-hour obstruction of John Nolen Drive; destruction of two iconic Capitol Square statues; the creation of an independent police monitor and oversight board; a school board vote to remove Madison Police Department officers from district schools; and the transformation of State Street into an outdoor gallery of provocative, inspirational and colorful graphics on the plywood-covered storefronts.

Protesting Israel

April 29-May 10, 2024

About 300 hundred members and supporters of Students for Justice in Palestine, or SJP, rallied on Library Mall, demanding the UW divest from companies active in Israel, and end student-exchange and study abroad programs there. Ignoring warnings about illegal encampments, they pitched about 30 tents in front of Memorial Library, which they named the “Gaza Solidarity Encampment.”

Wednesday morning, May 1, Chancellor Jennifer Mnookin authorized UWPD to end the encampment. After a final warning, about 70 police officers moved in. Some protesters resisted, a fracas ensued, and police made 34 arrests (including several professors), later charging four. But hours later, new tents popped up. By Monday, May 6, there were 50, which police didn’t disturb. Friday morning, hours before graduation ceremonies on May 10, SJP agreed to end the encampment and not disrupt commencement, and the university agreed to facilitate a meeting between SJP and the board responsible for the UW’s endowment investments; provide support services for students affected by the Israel-Hamas war; and bring at least one scholar from a Palestinian university to campus for the next three academic years (2024-2027). There were reports of antisemitic comments and threats, but no major incidents.

Stu Levitan is the author of three books on Madison’s history and president of the WORT-FM board of directors.

COPYRIGHT 2025 BY MADISON MAGAZINE. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THIS MATERIAL MAY NOT BE PUBLISHED, BROADCAST, REWRITTEN OR REDISTRIBUTED.