Rewind: From Telangana to Texas, a world without water

Benjamin Franklin once said, “When the well is dry, we know the worth of water.” That moment has already arrived

By Antara Das, Barun Kumar Thakur

The once-lush fields of Jangaon district in Telangana now crack under the weight of an unforgiving sun. Where golden stalks of paddy once swayed in the wind and maize crops stood tall, only withered remnants remain — a haunting reminder of the water that never came. In the village of Gangupahad, an elderly farmer runs his fingers through the parched soil, his face lined with worry, eyes teary. “Day after day, we looked to the sky, but no rain ever came”, murmurs a young farmer of Wadlakonda, staring at his failing crop, the debts mounting like storm clouds over his future.

The reservoirs that once nourished these lands — Ghanpur and Nawabpet — now lie depleted, their muddy bottoms exposed like open wounds. Yet, the final blow comes not from nature but from human decisions. Water from the Nawabpet reservoir, their last hope, is diverted to neighbouring constituencies, leaving Jangaon’s farmers with nothing but dust and broken dreams.

Similarly, in Maharashtra, a desperate crowd surrounded a lone water tanker, their voices rising in frustration. In the chaos, shouts turned into shoves and moments later, a man lay lifeless — all for a few buckets of water.

India, home to over a billion people, ranks 13th among the world’s most water-stressed nations. The 2018 NITI Aayog report revealed that 600 million Indians experience high to extreme water stress, with nearly 2,00,000 deaths annually due to inadequate access to clean water

In Delhi, at the peak of the last heatwave, people lined up with empty containers as taps ran dry. “We wake up at 4 am just to collect a few buckets of water before the supply cuts off. Some days, we don’t get any at all”, said a resident of South Delhi. The entire northern India faced a severe heatwave last May, which exacerbated water shortages, leading to over 50 deaths due to heatstroke and related illnesses.

These distressing stories are not isolated incidents but symptomatic of a worsening crisis gripping the world — from Telangana to Texas. But how much worse does it need to get before we take action? Can we afford to wait until even the last well runs dry?

A World Running Dry

Water, the essence of life, is waning at an alarming rate. Despite covering 71% of the Earth’s surface, only 0.5% is fresh and available for human use. The United Nations reports that 2.2 billion people lack access to safe drinking water, and by 2025, nearly two-thirds of the global population could face water stress.

India, home to over a billion people, ranks 13th among the world’s most water-stressed nations. As per the Central Groundwater Board reports, the groundwater extraction rate in India increased by approximately 24% from 2000 to 2020, leading to an annual water table decline from 0.5 m to 3.0 m during the same period. The percentage of critical and over-exploited aquifers grew from 25% to 37% over the 20 years, with States like Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh facing the highest depletion.

Across the country, water scarcity manifests in different, yet equally alarming ways. Climate change, unchecked urbanisation, industrial pollution and inefficient water management practices exacerbate this freshwater unavailability. In regions like the Indo-Gangetic Plain, where groundwater extraction is rampant, aquifers are depleting at an alarming rate, posing serious challenges to agriculture, livelihoods and long-term water security.

Even in South India, Chennai faced a Day Zero crisis in 2019 as its main reservoirs dried up, forcing residents to rely on expensive water tankers and deep borewells. Bengaluru’s booming population has overburdened its groundwater reserves, leaving many areas at risk of severe shortages. In Bundelkhand, recurring droughts have devastated farmlands, pushing farmers into debt and migration.

Ironically, Mumbai and Assam suffer from the paradox of excessive flooding during monsoons and acute shortages during dry months due to poor urban planning. These examples underscore the need for region-specific policies that consider local climate, population demands and water management efforts.

Beyond Dry Taps

Water scarcity and unsafe water are not mere inconveniences — they are silent catastrophes claiming millions of lives. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that 3.4 million people die annually from waterborne diseases. In India alone, 37.7 million people suffer from such illnesses every year.

In many parts of India, millions face an invisible crisis — drinking water tainted with arsenic and fluoride, silently poisoning those who consume it for longer periods. For women and children in developing nations, the crisis is particularly cruel. UNICEF reports suggest women in water-stressed regions spend an average of 200 million hours every day collecting water, often walking long distances and exposing themselves to health risks and gender-based violence.

For women and children in developing nations, the crisis is particularly cruel. UNICEF reports suggest women in water-stressed regions spend an average of 200 million hours every day collecting water, often walking long distances and exposing themselves to health risks and gender-based violence

Additionally, inadequate sanitation facilities in schools often lead to high dropout rates among adolescent girls. Therefore, ensuring universal access to clean water and sanitation is not just an environmental goal, it is a crucial step toward gender equality. Initiatives like installing community water supply points, investing in piped water infrastructure, and promoting women-led water management programmes can help bridge this gap and empower women and girls.

Water insecurity weakens the economy and reduces workforce productivity as industries struggle with unreliable water supplies. According to the World Bank, water scarcity could cost some regions up to 6% of their GDP by 2050, making it not just an environmental issue, but a major economic threat. Over-extraction of groundwater is turning fertile lands into barren deserts. Once-mighty rivers like the Ganges and the Colorado are drying up, leaving ecosystems and livelihoods in jeopardy.

Transboundary water disputes — like those over the Nile, the Indus, and the Colorado — highlight how dwindling resources are fuelling geopolitical tensions. Inter-State disputes over river water allocation, such as the Cauvery water dispute between Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, and Krishna water disputes among Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Maharashtra highlight the lack of a cohesive water-sharing framework.

Though India is the third-largest dam-building country in the world, with over 5,000 large dams, canal irrigation has declined since 1991, and groundwater now accounts for more than 60% of irrigation

The crisis also has disturbing consequences for ecosystems and biodiversity. Rivers and wetlands that once provided habitats for countless species are drying up, leading to drastic declines in aquatic populations. Fish species such as the Mahseer in India are facing critical threats due to decreasing water flow and pollution in rivers like the Ganges. In drought-stricken areas, trees experience increased mortality rates, impacting species that rely on them for food and shelter. The loss of wetlands, which serve as breeding grounds for birds and amphibians, disrupts ecological balance.

The renowned Keoladeo National Park in Rajasthan, once a thriving bird sanctuary, has witnessed a noticeable decline in migratory bird arrivals due to insufficient water supply. The construction of the Panchana Dam across the Gambhir River has significantly reduced water flow to the Ajan Dam, leading to water shortages in the park. Declining groundwater levels affect soil moisture too, leading to desertification and habitat loss for wildlife such as elephants and tigers, who rely on perennial water sources.

Is India Doing Enough?

Recognising the urgency, the Indian government has significantly increased budget allocations for water security. In the Union Budget 2025-26, the Ministry of Jal Shakti received Rs 99,503 crore, nearly doubling its previous allocation. Approximately 80% of rural households now have access to potable tap water, up from 17% at the Jal Jeevan Mission’s inception. In light of the remaining households yet to be covered, the government has extended the mission’s deadline to 2028, with an enhanced budget allocation of Rs 67,000 crore for the fiscal year 2025-26. Additionally, Rs 7,192 crore has been earmarked for the Swachh Bharat Mission (Gramin) to enhance sanitation and water accessibility.

To improve irrigation efficiency and promote sustainable agricultural practices, the Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchai Yojana (PMKSY) has been allocated Rs 8,260 crore. Furthermore, the Namami Gange Programme, dedicated to rejuvenating the Ganga River and managing water pollution, has received Rs 2,400 crore. The Atal Bhujal Yojana (ABY), aimed at sustainable groundwater management, has been extended to five additional States — Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Punjab, Tamil Nadu, and Telangana — with an increased budget of Rs 8,200 crore.

Additionally, the Repair, Renovation, and Restoration of the Water Bodies scheme has been strengthened to improve water conservation and irrigation potential in rural areas. While these investments highlight the government’s commitment, achieving water security requires integrated policies that combine infrastructure development with climate resilience, community participation and technological innovation.

According to the World Bank, water scarcity could cost some regions up to 6 per cent of their GDP by 2050, making it not just an environmental issue, but a major economic threat

India has made strides in adopting micro-irrigation systems to enhance water efficiency in agriculture, however, the overall adoption rates are still below potential. The India drip irrigation market was valued at approximately $934.8 million in 2024 and is projected to reach $2,064.2 million by 2033. Despite government subsidies, the adoption rate of drip irrigation systems remains relatively low, around 16%. Furthermore, India is the third-largest dam-building country in the world, with over 5,000 large dams. However, despite massive investments, canal irrigation has declined since 1991, and groundwater now accounts for more than 60% of irrigation. This suggests that factors beyond financial incentives, such as psychological and behavioural aspects, influence farmers’ decisions to adopt these technologies.

Moreover, India’s industrial sector (textiles, chemicals, thermal power plants, beverage production etc) uses around 40 billion cubic metres of water annually, often leading to groundwater depletion and pollution. Many factories discharge industrial waste into rivers. Sustainable business practices, such as zero-liquid discharge, water recycling, and responsible sourcing, must be enforced. Companies like Tata, ITC and Coca-Cola have initiated water stewardship programmes but such efforts need to be scaled up across industries. It’s praiseworthy that Nestlé and PepsiCo have committed to reducing water use per unit of production by 20-30% by 2030.

Also, India has strengthened rainwater harvesting mandates to address water scarcity, with a 2025 target of ensuring widespread adoption. The ‘Jal Sanchay, Jan Bhagidhari’ initiative aims to construct one million rainwater harvesting structures by the next monsoon. Several States have enforced regulations — Hyderabad mandates rainwater harvesting for properties over 300 sqm by 2025, Bengaluru requires it for new buildings on 40×30 ft plots, and Pune offers tax rebates for adoption. Despite these efforts, compliance remains a challenge, highlighting the need for stricter enforcement and awareness.

Chennai faced a Day Zero crisis in 2019 as its main reservoirs dried up, forcing residents to rely on expensive water tankers and deep borewells while Bengaluru’s booming population has overburdened its groundwater reserves

As Loren Eiseley aptly put it, “If there is magic on this planet, it is contained in water.” The challenge now is to harness this magic wisely, ensuring that it remains accessible for future generations through sustainable management and forward-thinking policies.”

A Future Where Every Drop Counts

Though the crisis is severe, solutions exist. Countries like Israel recycle nearly 90% of their wastewater, setting a global example. Israel’s National Water Carrier system efficiently transports water from surplus to deficit regions, serving as a model for other water-stressed nations. Singapore has developed a comprehensive water management system, including desalination plants and rainwater harvesting, making it nearly self-sufficient despite lacking natural water sources. The Netherlands has perfected water management with innovative infrastructure like dikes, dams and controlled flooding to protect against rising sea levels and water scarcity.

India must invest in similar water-efficient technologies, such as AI-powered leak detection and smart irrigation systems. Desalination plants, wastewater treatment and groundwater recharge initiatives must become mainstream practices. Individuals, too, play a role — fixing leaks, using water-efficient appliances, reusing greywater and practising rainwater harvesting can create a meaningful impact. Moreover, policies should emphasise equitable water distribution, ensuring marginalised communities receive their fair share. Strengthening international cooperation on transboundary water agreements is equally vital.

Time Is Running Out

The visionary polymath Benjamin Franklin once said, “When the well is dry, we know the worth of water.” For millions, that moment has already arrived. As we celebrate ‘World Water Day’ (March 22), let us commit to safeguarding this precious resource for our sustenance. If we do not act now, the next war we fight may not be for land or power, but for a single drop of water. The choice is ours.

(Dr Antara Das is Postdoctoral Research Fellow and Dr Barun Kumar Thakur is Associate Professor at Department of Economics, FLAME University, Pune. Views expressed are personal)

Related News

-

Telangana: National Thermal Power Corporation celebrates World Water Day

-

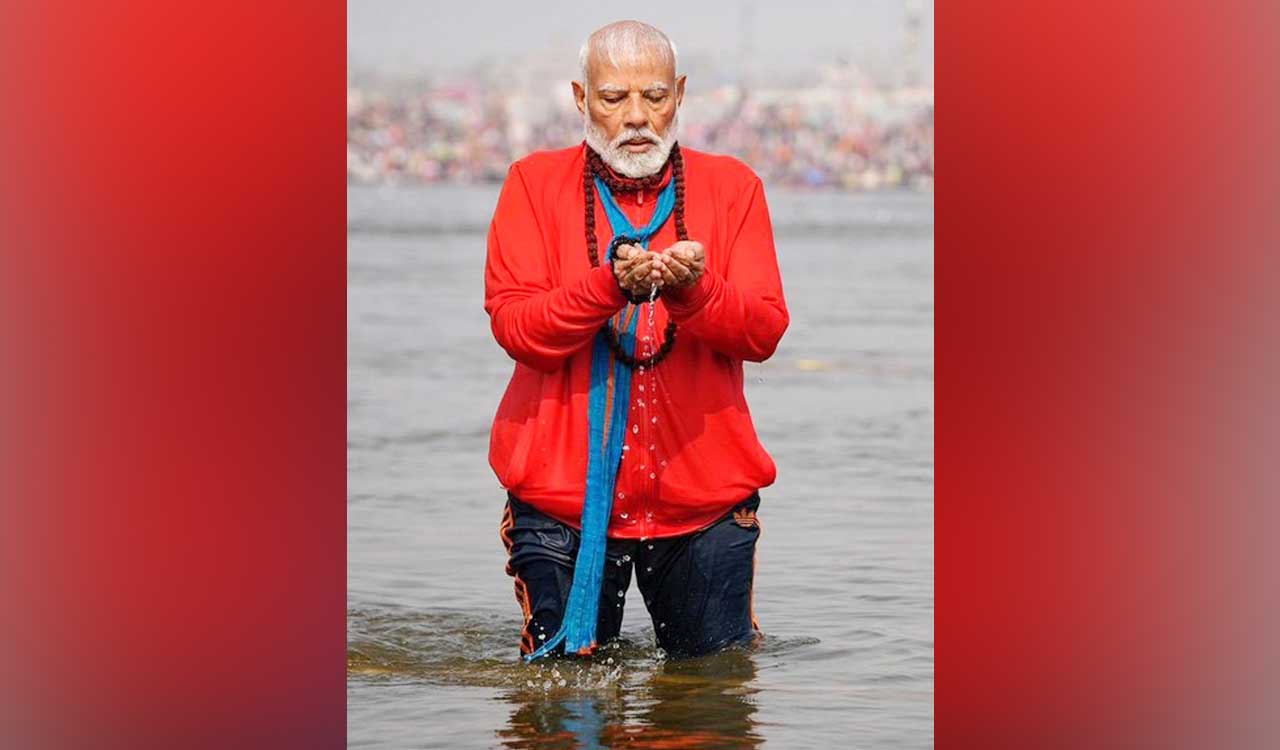

World Water Day: PM Narendra Modi reaffirms commitment to conserve nature’s vital element

-

Rewind: Indian lion languishes in its lair

-

Telangana: Over 200 villages identified to be vulnerable for facing drinking water crisis in Asifabad, Adilabad

-

SBI clerk prelims result 2025: To be released soon on this website

32 seconds ago -

FC Goa’s Brison Fernandes Shines Ahead of ISL Semi-Finals

18 mins ago -

Naga Chaitanya launches ‘MAD Square’ trailer

37 mins ago -

Kothagudem Temple Board row: Villagers demand to stop swearing in ceremony of Board of Trustees

45 mins ago -

RBI Governor sees AI as key tool to combat money laundering

54 mins ago -

BRS MLCs stage protest over Congress government’s “gold” failure

59 mins ago -

BRS stages walkout alleging “unparliamentary language” from Bhatti

59 mins ago -

CUET UG 2025: Correction window remains open till this date

1 hour ago