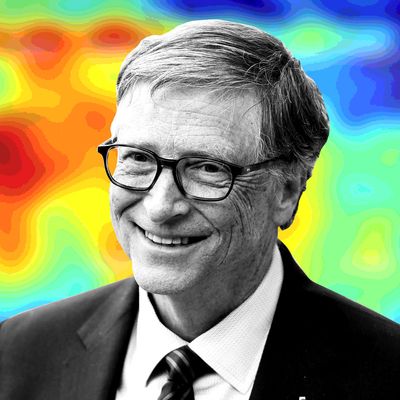

On September 23, the United Nations will open its Climate Action Summit here in New York, three days after the Global Climate Strike, led by Greta Thunberg, will sweep through thousands of cities worldwide. To mark the occasion, Intelligencer will be publishing “State of the World,” a series of in-depth interviews with climate leaders from Bill Gates to Naomi Klein and Rhiana Gunn-Wright to William Nordhaus interrogating just how they see the precarious climate future of the planet — and just how hopeful they think we should all be about avoiding catastrophic warming. (Unfortunately, very few are hopeful.)

Today, September 17, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation released its annual “Goalkeepers” report — a data-heavy status update measuring global progress toward the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals. (It always doubles as a report card on the work of the foundation.)

This year’s edition focuses on inequality and the ways that gender and geography remain obstacles to opportunity in much of the world — “We were born in a wealthy country to white, well-off parents who lived in thriving communities and were able to send us to excellent schools,” the report opens, before moving on to focus on primary health care and “digital inclusion” (the way that technology has helped the distribution of cooking gas in India, for instance).

But it also devotes a significant chapter to climate change, a growing focus for Gates and the foundation, and in particular climate adaptation — the challenge of how to actually live in a world transformed by global warming. As an investor, Gates has backed dozens of companies developing new tech to at least help slow down temperature rise — from next-generation nuclear to new battery technology and beyond. But the foundation has always directed its giving toward what it considers “market failures” and the plight of the world’s poor, and so Gates’s philanthropic work on climate change is less focused on stopping global warming than on dealing with it.

On August 5, in Seattle, I talked to him about balancing the prerogatives of adaptation and mitigation, the scale of the challenge of climate change and whether we have any realistic chance of avoiding catastrophic levels of warming, and just how punishingly unequal the impacts of climate change will be when they do arrive.

You and Melinda describe yourselves as “impatient optimists.” The impatient part is especially interesting to me because I come at some of these big questions from climate, and the timeline there really has changed my perspective about the broad trajectory of progress in the world. Has it changed yours?

If you asked Warren Buffett still what he worries about the most, he’ll talk about nuclear weapons.

In a way, that is rational.

Yeah, it’s a little scary, actually. The current generation is thinking about climate change appropriately, but we didn’t actually get rid of those nuclear weapons.

But putting aside climate change, the trajectory and nuclear weapons and big pandemics and bioterrorism, all of which are worthy of attention, the general trajectory of the world is very positive. Scientific understanding has given us new vaccines and new drugs and better seeds, cheaper ways to make fertilizer, digital ways that we can track: Is the government spending its money properly? Are people who go to the health clinic getting treated the way they want? So there’s a lot of things that have us on this very positive arc. In fact, the last 30 years, since 1990, we’ve made more progress on reducing child mortality than at any time in history.

But how about climate change?

Climate change is a super-important topic, and sadly the mitigation part, which is very, very important, has gotten 95 percent to the attention — though not enough that we can say we’re in good shape there. The greatest expert on energy is Václav Smil. Whenever you spend time with Václav, he’s like, “Oh, yeah? You’re going to do what in 20 years?”

I was just reading a piece of his earlier on that this morning.

His stuff is so good. You can’t get enough of him. He’s coming out with a new book …

Growth, yeah.

Super-good. It’s just a reminder that the modern economy is about energy intensity. This idea that we’ll take 100 million barrels a day and just not use them, that we’ll just say, “No, no. No, thank you” — it’s very hard.

If we are imagining a world in which we take some dramatic action and engineer some kind of meaningful solution to this challenge, what does that look like to you? How big a part of it is nuclear power? How big a part of it is carbon capture? How big a part of it is new cement? How do you see that big picture?

There’s a long answer to that. I would like to help educate people on what a plan really means. A plan involves looking at all the sources, electricity, transport, industry, buildings, and land use/agriculture and really saying, “Okay, what are the possible paths that get you to these dramatic reductions, and therefore what are the missing inventions?” Fortunately, there’s not any one path. If you don’t have nuclear and if you don’t have a storage miracle, it’s very, very hard, because basically what you have to do is have electricity be used for many, many, many things like all building heating and cooling that today, you use natural gas or coal for it directly.

So, first, you have to assume you can make electricity with zero emission. Then you assume you can make the electric sector almost three times bigger than it is today — these are mind-blowing investments. I want to help educate people because I have not seen anything that’s worthy of the word plan because a plan has to involve not just the U.S. doing something.

Of course, yeah.

You have to convince middle-income countries. I think of India as paradigmatic, because it’s big enough to count and it’s poor enough. They deserve to have air conditioning. I mean, they’re getting very high wet-bulb temperatures. Jesus Christ, by 2070, there could be just a massive number of people dropping dead in the streets.

So a plan that really addresses the global issue has to bring what I call the green premium for all of these various goods and services down dramatically, like over 90 percent.

What’s the green premium?

What would green cement cost today? What would green steel cost today? What would green beef cost today? It’s great that people care about the issue, but it’s a very complex issue. And, unfortunately once they hear about how hard it is to solve and how expensive it is to solve, I hope their resolve isn’t … When diesel prices got increased 15 percent in France, more near-term considerations came into play.

The international picture there is so important because each individual nation, with the possible exception of the U.S. and China, is contributing only so little, and so they have less motivation to act dramatically. Given all that, what do you think should count as success, and what should count as failure? Do you credit a goal of two degrees? Do you think that that’s overly optimistic? How do you define success in the climate story?

There are no magic numbers. The smaller the temperature increase the better. People who say that this number’s associated with “It’s all over, don’t even try.” No, that’s not true, but wow. As that number goes up three, four, the amount of sea rise you lock in, the amount of ecosystem loss that you lock in, it gets to be super, super high. So you just don’t want to run the experiment.

It’d be great if we could stop at two degrees. Unless there are huge surprises on scientific advances, I just don’t see it happening, but who would have said that [about] radio waves or wireless or chips with a billion transistors? We know Václav is not optimistic. Yet to really get people engaged, you have to say, “Hey, we can really achieve this thing.” The fact that the R&D budgets weren’t even being discussed …

R&D does seem very important.

I mean, not to be egocentric, but that was put on to the Paris climate agenda because I went to France and said, “Hey, here’s something you get to do that’s going to be different.” Then it turned out that was the way of getting Modi to actually come to the thing, which was fantastic.

Especially given the impacts expected to India you mentioned earlier.

Nathan Myhrvold and Ken Caldeira wrote an article that really shows that, if you take the very best case, a 1.5 degree case — which, we’re not in that universe, period — you don’t have a cooler year for 50 years. If you take a three-degree case — and even that would require us to do better than we’re doing today — you don’t have a cooler year for 100 years.

The scientific community, in terms of dealing with disasters, is always very cautious to not be an alarmist group. And so the general literature, because it’s done by scientists, understates these things by quite a bit. Take permafrost melting and methane release. Well, we thought that was a problem. Then we didn’t think it’s a problem. Now, actually, we’re back to thinking it is a problem. There are things like the Atlantic circulation. For a while we thought that was a problem. Now we don’t think it’s a problem. Sudden ice collapse, we didn’t think that was a problem. Now in the geological record, we actually do think sudden ice collapse may be a serious thing in parts of Antarctica.

If people keep their current seeds, then agricultural productivity will go down a lot. Monsanto has different seeds for different parts of the U.S. depending on the temperature, and, already, the seeds that they used to give to Texas, they now give to the Midwest. The beef lots — they used to fatten cows down in Texas, now nobody does it anymore because it’s too hot there, and so all the meatpacking is moving north. It’ll be in Canada.

Relatively soon.

By 2060 or 2070, for decent productivity, it has to go up to Canada.

It’s clear that if you can’t change the seeds you use, then this is a disaster, because weather is already a problem for subsistence farmers. It’s always just a question of how many years do they have a super-bad crop. Rich-world farmers can take their average output and live on the average output because they have a savings bank or crazy government programs, so they don’t face starvation. Poor-world farmers already behave in ways that at first we thought were kind of crazy where they diversify their crops in a way that makes their average output really low. But once people thought about it and realized, Oh, they’re trying to really reduce the probability that the number of calories they’ll have for themselves or their children …

Will disappear entirely.

So they grow way more cassava than they should. Cassava is a very low productivity plant, but it’s an emergency crop because it can withstand worse weather conditions than every crop but, say, sorghum. Sorghum’s really good with heat.

But we need a huge improvement in the seeds to deal with drought, to deal with heat. I don’t know if we can get it or not, to be honest. I’m an optimist. The last time the world worried … Paul Ehrlich wrote The Population Bomb, predicting everything was going to turn out Malthusian. He was wrong. Two things happened that he and nobody else knew.

Norman Borlaug happened.

Well, the Green Revolution, which Borlaug was key in, and people chose to have less children. So the population estimates were way too high and the total calories produced because of the new seeds and fertilizer. Those seeds require massive amounts of nitrogen. If you use those seeds without nitrogen, you get hardly anything, and Africa has very little access to fertilizer. They have the worst soils in the world, and they’re equatorial.

That suggests you can address some of these issues with regenerative agriculture practices, right, in addition to designing better seeds?

There are things like no till, where the amount of soil erosion is greatly reduced. Hand farming, though, never has the erosion problems that mechanized farming does.

We also need to get air conditioning into the equatorial regions, particularly urban equatorial regions, and we need to get the crops so that they can withstand drought and that your good years you have a lot more productivity. You’re going to have bad years. There are years where rain doesn’t come, and there’s no seed in the world that can do a damn thing about that. There’s a few things that are miraculous. Like, we came up with this form of rice. Usually when rice gets flooded, it dies. We funded a thing where the rice just goes into stasis. Then when the water goes away, it goes back and it grows. That’s one of those things where you have this field over here where there’s nothing and this field over here where there’s really something. But that is so rare that you get something like that.

It’s crazy that the world isn’t focused on making better seeds and talking through this adaptation stuff. There’s a recent thing about how as you raise CO2 levels that the micronutrients in the plants goes down. There’s only $5 million of random messing around that was ever spent to look at that. Now it looks like we’re going to have to go and fund a real study to see, Is that true across all crops? Why would that be true? It’s completely out of the blue, completely unexpected, and may or may not even be true. If it is true, our whole malnutrition thing is going to be even more deeply challenged.

So big picture?

Huge uncertainties, huge underinvestment. Even when you get people who are activated on this issue, you say to them, “Hey, what do you know about adaptation?” There was a thing called the Green Climate Fund, which was supposed to be $10 billion. Obama got a little money to it, but then it —

It died, basically.

I think he got $1.6 billion before he left office. But if you look at the stuff they are going to spend their money on, it’s ridiculous stuff that are complete rounding errors. They’re not systemic things like better seeds or better air conditioning. They’re just a little project here and a little project there, which — it doesn’t add up to anything. So climate change is definitely a footnote. And just because we’ve met challenges in the past doesn’t guarantee that we’ll meet challenges this time. Can we build new nuclear reactors that are super-safe? Will the world accept those? I don’t know. I’m the world’s biggest funder of that dream, but even I would say that our chance of success …

What is it?

Say our chance of success technologically is like 70 percent, then our chance of convincing the world to take advantage of it, say that’s like 40 percent, so you have a 28 percent likely thing, which would be super-helpful because it’s 24-hour reliable energy. You can’t afford not to do it, but the world is crazy. The world is not investing … Even China, which is investing the most, isn’t investing as much as they should.

They pulled out of working with TerraPower, right?

The U.S. forced us to not work with China, so they’re on their own now, and I don’t know what they’ll do. Will the U.S. support us to build a pilot plant here in the U.S.? If you had a big climate initiative where there were, say, $20 billion of R&D being spent, if 5 percent of that could go to nuclear, that’s more than enough money for this dream to be fully pursued. Anyway, we’re trying to get the seed stuff funded. The seed stuff, some of it, depending on how you define the word GMO …

It has a similar problem as nuclear.

Yeah. The Europeans who are the most generous donors in the world, giving in some cases 0.7 percent of GDP, which is this level that the movement tried to get everybody up to … Anyway, some of them are very uncomfortable with the scientific techniques. Yes, there’s still room to do a better job of conventional breeding, but when you’re dealing with the type of temperature increase we’re talking about, no way. You are going to have to do genetic modification.

Well, and there’s no real scientific argument against it.

No, there’s not. Yes, everything should be subject to review just like medicines are, but that one’s a troubling one. Will those things get out of adoption? We don’t really care whether Europe adopts them or not. We’re not trying to tell them that they should adopt them. We’re just trying to have them let Africa and poor countries in Asia, but mostly Africa —

Is there that kind of resistance in the developing world to GMOs, or is mostly a wealthy country issue?

They are completely confused. What Europe does is they say, “Okay, if you want to export to us, if we detect even 0.1 percent of GMO in your exports, we’ll ban your exports.” That’s really kind of unfair for the crops that Africa tries to export. The U.S., by and large, encourages Africa to be open-minded.

There’s two issues on GMOs. One is, is there a commercial problem that you become dependent and that U.S. seed manufacturers charge too much money? Then there’s, is there a health risk involved? But the stuff we’re talking about doing is all public-domain stuff, so we have to tell people, “Hey, this is not Monsanto.” Now, I have nothing against Monsanto. In fact, they’ve contributed more to the base understanding of these things than any company in the world.

The big theme of this year’s Goalkeepers’ Report is, essentially, inequality of opportunity. The thing that I was personally struck by was the matter of inequality within countries in the global South. We hear a lot about inequality within countries in the global North and between the countries of the global North and the global South, and much less about how one region in Nigeria could be performing so much better than another region in Nigeria. How important is it to address those inequities in the broader fight against inequity globally?

You have the rich countries who get to fund innovation and fund aid. Then you have middle-income countries like China that have done amazingly well, and they have their explicit goals. I want to say they have 42 million people still living in extreme poverty, and by 2022 they’ll halve that. They have a department that I’ve gone and met with that we actually work with that does it in a very Chinese way, but they have a list of the 42 million people, and they’re saying, “Oh, this one has to move.” Not many governments have the tools at their command that they have. And there, extreme poverty will be very low — though there will still be a sort of a seaboard-to-interior-type differential.

In India, it’s a North-South. The South is way better. Kerala is below replacement rate in population growth. Whereas Uttar Pradesh is still 3 percent growth rate. In India, there’s a part of India that’s like sub-Saharan Africa, a part of India that’s more like coastal China, all within one country. And within India, it’s really great, because there is this sense of interstate competition, and practices do spread. The jealousy factor of, “Oh, if they can do it, we can do it,” is really useful. You cannot go to India and say, “Oh, you’re worse than China.” That’s like, who cares? That’s just insulting for you to even notice that. But saying, “Hey, your state is almost as good as this other state, if you would just do this and this” — that’s different. Chief ministers really respond to the sub-national sense of, “Oh okay, they can do it. I’m going to try and do this.” So it’s a very positive dynamic.

Nigeria’s a very scary one where the South is way better than the North. The population growth is almost entirely in the North, with a broken-down primary health-care system. The North of Nigeria is really bad. The state is almost not there. They just don’t raise enough money, and they don’t spend the tiny amount they raise very well at all. So these differentials are really gigantic.

You get to Somalia or DRC, then they aren’t as gigantic. Those are just very, very tough places. But there’s various statistics about that [that] more people in extreme poverty won’t live in the worse-off countries partly because Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nigeria, Indonesia, India, have a lot of population, so there’s a lot of very poor people in those countries because the population combined in those countries is double the balance of sub-Saharan Africa.

And Nigeria in particular is growing really rapidly.

The population is growing. The economy, they did this base adjustment. They’re still very oil dependent. Nigeria’s 200 million people, so it really counts — that’s 200 million of 840 million people in all of sub-Saharan Africa in one country. It really counts. Almost every disease the foundation works on now, it used to be India was No. 1. Now, for most of our diseases, Nigeria is No. 1. Even the rates of malarial deaths in Nigeria are amongst the highest in the entire world.

On top of which, the babies are choosing to be born in the tough places. That’s true if you do it on a continental basis where today 22 percent are born in Africa. It goes to 50 percent by the end of the century. But even if you take on a country basis, it’s the poorer countries, and even if you take within the country, like in Nigeria, the babies are choosing to be born in the North. Then you have climate sitting right on top of that.

Can you take lessons from, say, the South of Nigeria and use them to help the North? What are the obstacles there?

The number of meetings I’ve been in where I’ve said that and people are like, “Oh, no.” But, yes.

How?

If you trust government to spend money well, then you’re willing to be taxed. If you think that money is totally misspent, you aren’t. And so you get these equilibrium conditions either within a country or within regions of a country, where people have so little expectation that the government will work on their behalf. Everybody joins a gang, and you hope that your gang gets elected because they won’t grow the pie for everybody, but you’ll just get a disproportionate share of a very small pie. That’s what democratic politics is in many poor countries.

How big a part of that problem of those inequities is gender? When you think of these challenges, how big a focus for you is making sure that women are educated at the same levels and also family planning [is] liberated from the burdens of all that stuff?

If you look at countries dropping down their population growth or raising female education levels or reducing child and infant mortality, those three things are super-correlated to each other — like super-correlated.

Women’s groups are this amazing tactic. Because an individual woman saying “Hey, I went to the health-care clinic and the line’s too long or the vaccines weren’t there” has just no voice. In fact, sometimes they’re not even allowed to leave their hut and go get the vaccinations. So if you create women’s groups, even that basic idea of “We’re allowed to go to the health center” or you get told vaccination is this very important thing to do, that works out very well. Letting the women have [their] own digital money account, that works out pretty well.

These things take time, so some of the cultural issues are tough. The women tend to meet with the women, and the men tend to meet with the men as you’re going into these villages, so that saying “Poverty is sexist” is really strong. That is, women are the most disadvantaged by the power and balance in these poor countries. And there are very few exceptions. As countries get richer, Japan’s not a perfect case, but by and large, as you get richer, your gender empowerment gets stronger. You can use gender empowerment to drive the other things. Women’s education, of all things, first getting them all into primary school, which the world’s done a very good job on. Except the Sahel, by and large, elementary-school participation rates are balanced. If you get to secondary, that’s less the case.

Pulling out of places like Nigeria and the Sahel — the subject of inequality is now a much bigger part of our conversation in a country like the U.S. We’ve been talking about inequality for a while, of course, but it seems to me that in the past year there’s been a renewed focus maybe powered especially by that Anand Giridharadas book, the Rutger Bregman speech at Davos about the value of philanthropy in the world that we live in today. I think everybody, even people who criticized that system would say, “The Gates Foundation is the gold standard here,” and I totally agree. I wonder how you feel about the broader structure of society, though — whether there are things that philanthropies can do that governments can’t do. I know you support higher taxation generally but wonder whether you think that we’re in a healthy place where so much of our most ambitious investment and R&D and thinking is being taken up by private philanthropists rather than by the public sector.

Well, overall, philanthropy is pretty small. In the U.S. economy, it’s 2 percent, and a third of that’s just giving to your church, so it’s a very small part of the economy, and so you can’t expect it to do ultramagical things. You could try getting rid of it and give that to some bureaucrat. Yes, government needs more money. The safety net has constantly been going up, and we’re rich enough the safety net can go up more. We can have more progressive taxation. We can reduce concentration of wealth through things like estate tax; the wealth tax maybe, maybe not. At least people are discussing it now. Is that really particular? Does it work? In the last ten years, Europe got rid of their wealth taxes. And you may need cooperation between countries to really do it well because of leakage effects.

Should people be allowed to give to their church? Probably. United Way for local social services? Probably. Should they get tax deductions? All these tax issues, that’s all up in the air. If somebody wants to be less generous on the tax deductions, that’s okay. The way the estate tax works, where whatever you put into a foundation is exempt from the estate tax, it does increase the level of giving. Now, do you get back commensurately what you want from it? It makes people more tolerant to the very high estate tax, which [is] why I kind of like it.

Anyway, the democratic process will resolve that. Recently, taxes become more favorable to the rich, although people are confused about that. But, honestly, they did, so it’s kind of this weird thing. I think most of the noise is about progressive taxation and should the people of these big fortunes have had to pay a lot more taxes? Then there’s criticisms of philanthropy, and of course there should be criticism. We benefit from a lot of criticism. Should we put more money into this? More money into that, those kinds of things? I’m so involved in philanthropy, it’s hard for me to be objective about it.

More From This Series

- ‘Any Further Interference Is Likely to Be Disastrous’

- ‘We Are Living in a Reality That Is Fundamentally Uncanny’

- ‘The House Is Burning Down and We’re Just Sitting Around Discussing It’